Where the Chaos Goes

Rachel Shu's Blog

Visual Portfolio

My Admonymous

Subscribe to RSS/Atom Feed

Blogroll

Astral Codex Ten

Nintil

Aceso Under Glass

Good Optics

Video games are philosophy's playground

by Rachel Shu

Status: in progress

Meaningfulness:

one of my better essays

Crypto people have this saying: “cryptocurrencies are macroeconomics’ playground.” The idea is that blockchains let you cheaply spin up toy economies to test mechanisms that would be impossibly expensive or unethical to try in the real world. Want to see what happens with a 200% marginal tax rate? Launch a token with those rules and watch what happens. (Spoiler: probably nothing good, but at least you didn’t have to topple a government to find out.)

I think video games, especially multiplayer online games, are doing the same thing for metaphysics. Except video games are actually fun and don’t require you to follow Elon Musk’s Twitter shenanigans to augur the future state of your finances.

(I’m sort of kidding. Crypto can be fun. But you have to admit the barrier to entry is higher than “press A to jump.”)

The serious version of this claim: video games let us experimentally vary fundamental features of reality—time, space, causality, ontology—and then live inside those variations long enough to build strong intuitions about them. Philosophy has historically had to make do with thought experiments and armchair reasoning about these questions. Games let you run the experiments for real, or at least as “real” as anything happening on a screen can be.

So far, philosophy of video games has mostly focused on ethics (is it bad to kill NPCs?) and aesthetics (are games art?). These are fine questions, I guess, but they’re missing the really interesting stuff. Games are teaching us to navigate metaphysically alien worlds with the same ease that previous generations navigated their single, boring reality, and we’re barely even noticing.

I. Space

Start with the obvious example: spatial representation.

Imagine trying to explain The Sims to your great-grandmother. “Well, you see, you’re looking down at this house from above, and the roof isn’t there even though the roof exists, and you can see all the rooms at once, and you move your little person around by clicking where you want them to go, and—”

She would think you were describing some kind of fever dream. But if you’ve ever played The Sims, or Age of Empires, or any top-down game, you know exactly what this perspective feels like. It’s not even slightly confusing. You just… know how to navigate 2D space viewed from above with transparent roofs. This is a completely unnatural way to experience space, and you learned it without even noticing.

Now consider a kid who plays Minecraft (first-person 3D), Hollow Knight (2D side-scroller), and Mario Kart (third-person 3D with a camera that’s doing absolutely wild things around corners). They’re casually switching between incompatible spatial ontologies multiple times per day. Each game has different rules about what space is, and they don’t get confused even once.

Games like Portal make this extra weird by giving you geometries that can’t exist in our physics. You can look through a portal and see a room that’s “far away” in terms of walking distance but right in front of you in terms of line of sight. An object can be halfway in two rooms that are distant in the level geometry but adjacent in portal-space. The Companion Cube doesn’t care about your human notions of spatial continuity.

I think we’ve collectively underrated how wild this is. We’ve basically done for spatial reasoning what literacy did for memory—extended it beyond anything our ancestors would have thought possible.

II. Time

Temporal representation in games is less developed than spatial stuff, but it’s still pretty interesting.

The basic distinction is between turn-based and real-time games, but there are way more variations than you’d think. Real-time strategy games typically run on sped-up time (that “day” took three minutes). Turn-based RPGs often have weird time during combat (everyone’s turn happens “simultaneously” even though you take them sequentially). JRPGs will let you spend six hours in menus while a guy winds up to punch you and time is presumably just… frozen?

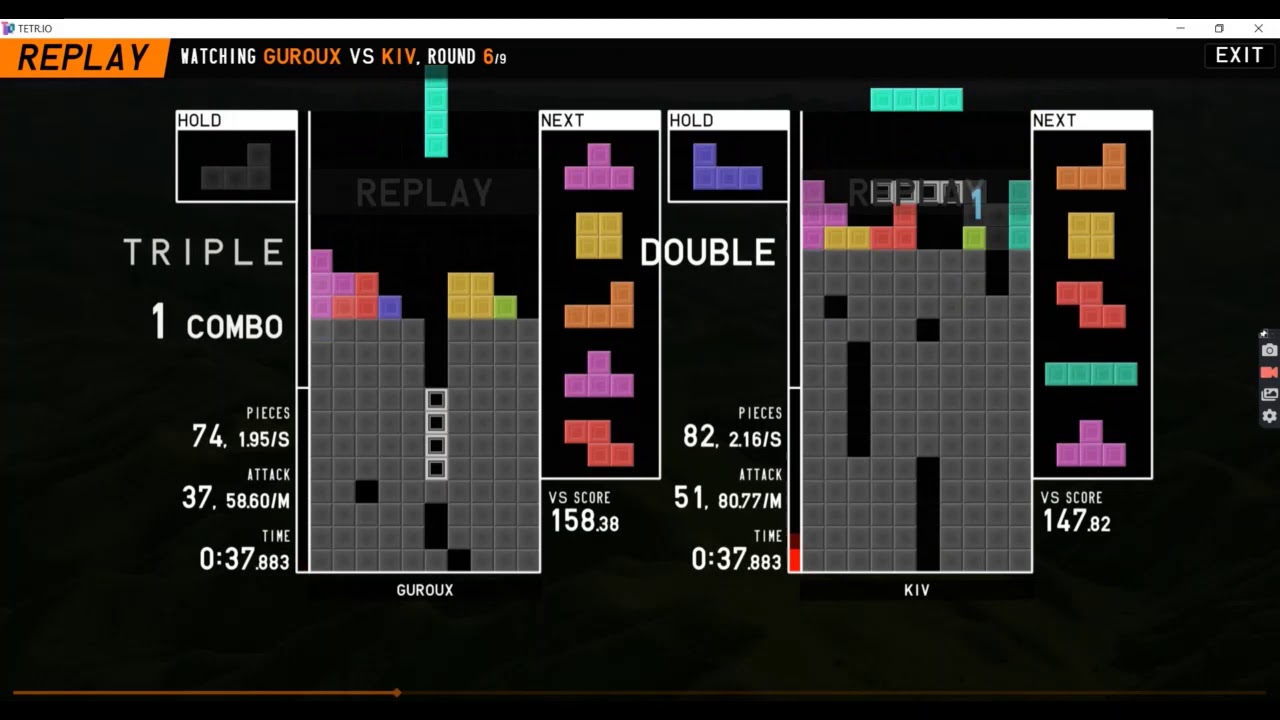

Multiplayer Tetris is a nice simple example of how multiplayer can make time weirder. In single-player Tetris, time is linear and local—your pieces fall, you place them, newer pieces typically end up on top—that’s the whole causal structure. But in multiplayer, your actions send “garbage” rows to the bottom—the past—of my board. Events in your reality retrocausally influence events in my reality. You’re both experiencing time, but you’re not experiencing it together in the way you’d experience time with someone sitting next to you.

Then you have games like Achron, which just throw out linear causality entirely. In Achron, you can send units back in time to past battles and retroactively change their outcomes. Your opponent can respond by sending their units back further, so the “real” history is whatever emerges after both sides stop editing the timeline. Causality becomes a negotiated product rather than a fixed ordering.

(I have no idea if anyone actually plays Achron. I just think it’s conceptually beautiful.)

III. Ontology

Most video games are structured in a way that takes the piss out of Plato and nobody comments on it because it’s so normal.

There are prototypes of entities (the idea of a Goomba, stored in the game code), and each entity you encounter is a manifestation of that ideal form. Is this particular Goomba more or less “real” than the abstract Goomba-template? That’s not even a meaningful question—one is in the code, one is in the game state, that’s all. Many game engines have tools that let developers smoothly switch between different levels of representation.

But different genres push you toward radically different ontological commitments, and I think this is underappreciated.

Systems-focused games like Factorio invite you to embrace structural realism. What’s real isn’t the individual inserter arm or smelter—it’s the throughput of your iron processing, the ratio of green circuits to red circuits, the bottleneck in your oil production. The game wants you to think this way. It overlays production graphs over the game world. Individual entities matter only as instantiations of rates, ratios, and flows.

(If you’ve never played Factorio, imagine if every economics textbook made you build the supply and demand curves out of little machines, and also there are aliens trying to destroy your curves, and also it’s 3 AM and you’ve been playing for six hours and you just need to fix this one throughput issue and then you’ll go to bed. That’s Factorio.)

Character-driven RPGs do the opposite. They’re deeply committed to object realism: specific people with specific histories are what’s real.

In Disco Elysium, Kim Kitsuragi is technically just “companion NPC class with loyalty stat at 75%” or whatever. But the game relentlessly focuses you on his particularity—his Aerostatic Pilot Qualifications, his damaged motor carriage, his carefully maintained political neutrality. The systems (skill checks, thought cabinet) exist to reveal character, not the other way around. When you care whether Kim approves of your choices, you’re implicitly treating him as ontologically primary: a person who happens to be embedded in game systems, rather than a bundle of stats that creates the appearance of personhood.

I think games are quietly training players to be ontological pluralists—to switch between “everything is patterns and flows” and “specific individuals are what matters” depending on context, without getting confused about which mode they’re in.

IV. Modality

Video games make modal logic visceral in a way philosophy professors can only dream of.

(Actually, Spider-Verse and Everything Everywhere All at Once do this too. Somehow a bunch of really interesting philosophy-fiction got marketed as sci-fi movies and people don’t think twice about it, even when every single remotely sciencey device in the movie is an implausible macguffin excuse to go explore some David Lewis world. But that’s a rant for another time.)

The thing about possible worlds is that in philosophy they’re always just theoretical. “In possible world W, you chose the other option” is a sentence you write on a whiteboard, not a place you can go visit. But in video games? You just press F9.

Every save file is its own world. When you’re playing an RPG, each playthrough is a path through a branching tree of possibilities. You chose to save the village, so you’re in World-A. But World-B, where you burned it down to see what would happen, is sitting right there in your save folder. It’s not a thought experiment. It’s an actual simulated timeline that diverged from yours, and you can go visit it whenever you want.

This makes modal logic into a design decision, which is kinda cool. How many worlds are there? You can just choose how many worlds there are.

Roguelikes with permadeath are basically modal fascists. You get one timeline, one set of choices, and when you die that world is gone forever. There’s no accessibility relation between worlds because there’s only one world at a time. You can start a new game, but that’s not “reloading”—that’s creating a fresh universe. Your previous character is just gone, erased, sent to whatever afterlife deleted save files go to. (Probably the same place as my childhood Pokemon team. RIP Starmie.)

Meanwhile, games with quicksave are modal anarchists. You can branch at any moment. Every single decision point spawns a new possible world, and they’re all equally accessible. You can explore the entire branching structure if you want. Save, try option A, reload, try option B, reload, try punching the quest-giver in the face just to see what happens. (This is called “being thorough.” Or “having ADHD.” Same thing.)

The really interesting cases are in between.

Visual novels will sometimes lock endings behind prior playthroughs. You can’t access the “true ending” route until you’ve completed endings A, B, and C first. You’re constraining the accessibility relation! The game is saying “possible world W is only accessible from possible worlds X, Y, and Z.” It’s taking a position on the structure of modal space and implementing it as a menu option.

Some games lean even harder into this and make the player the only object that persists across timelines. Your character dies and forgets everything. But you, the player, remember. You know the layout. You know the boss patterns. You know not to trust the guy in the third room because in World-B he betrayed you.

This creates a weird split-level ontology. From inside the game world, you’re just another character who keeps having really good intuition about things that haven’t happened yet. From outside, you’re a trans-world entity with knowledge that shouldn’t be possible in this timeline.

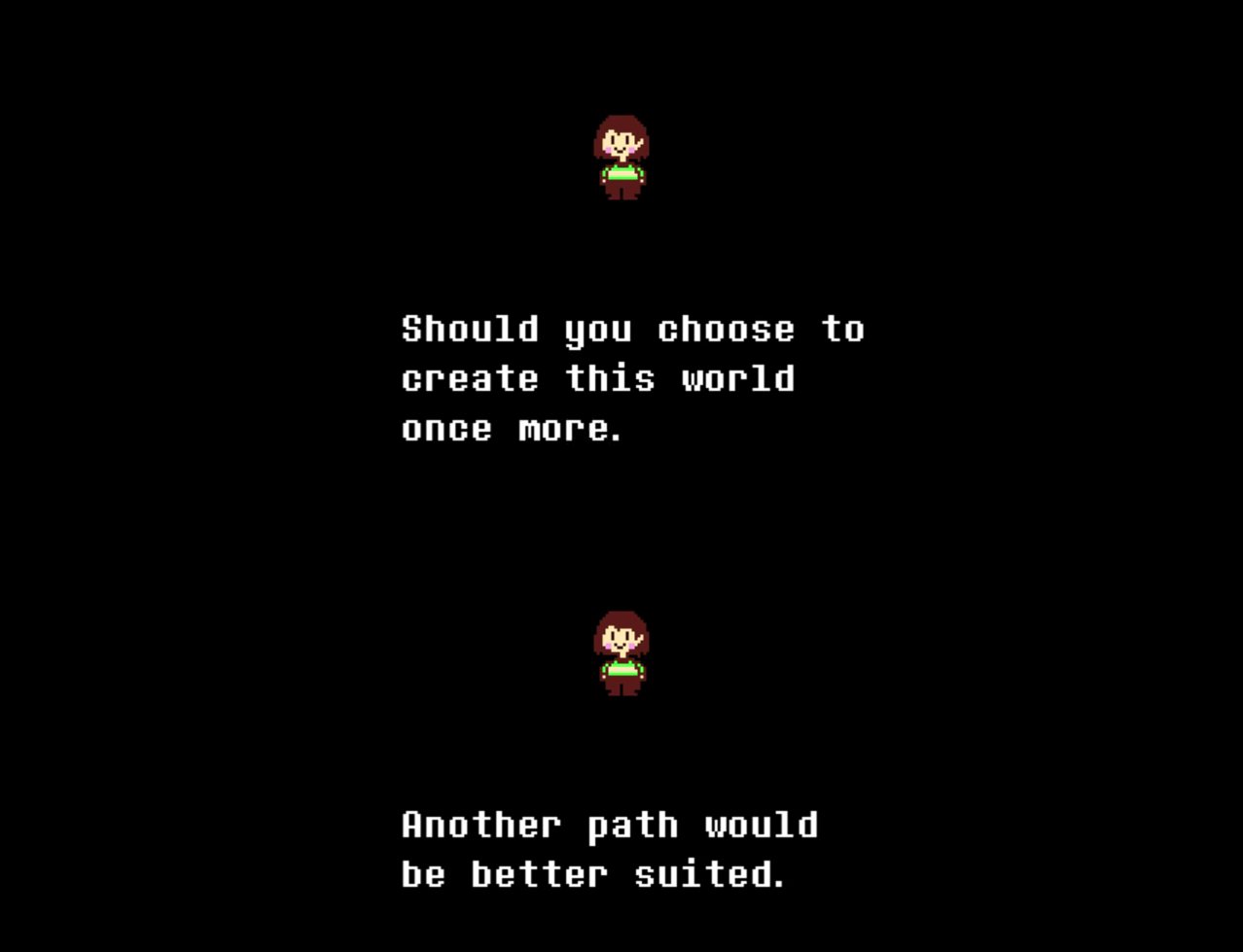

Undertale does something genuinely clever with this. The game tracks how many times you’ve loaded your save, and late in the game, characters call you out on it. They know you’ve been resetting. They know they’re in a timeloop. The game’s final moral argument hinges on the fact that you, uniquely, remember all the timelines, which means you have responsibilities they don’t.

The characters are asking: if you can see all possible worlds, are you obligated to find the best one? Or is it okay to keep reloading because you’re curious what happens if everyone dies?

This is basically the core problem in modal ethics except instead of discussing it in a seminar room you’re being accused of murder by a skeleton who’s surprisingly emotionally articulate.

I think the permadeath versus quicksave distinction is secretly doing a lot of philosophical work that we don’t usually acknowledge.

Permadeath games are saying: your choices have weight because they’re permanent. The possibility space is real but the worlds are mutually exclusive. You can’t see what-if because you’re stuck in what-is. This is how actual life works, and it’s why decisions matter.

Quicksave games are saying: exploring the space of possibilities is itself valuable. The point isn’t to commit to one timeline—it’s to understand the full branching structure. Every decision reveals information about the game’s design, even the “wrong” decisions. You’re not playing to win, you’re playing to map the possibility space.

And people have strong preferences about this! Some players find quicksave tedious—if you can just undo any mistake, why do mistakes matter? Other players find permadeath stressful—why would I want less information about how the game works?

This isn’t just about difficulty or playstyle. It’s about which modal metaphysics you find more meaningful. Do you want your choices to matter because they’re irreversible? Or do you want to explore freely because constraint feels arbitrary?

I don’t think either side is wrong. I think they’re just prioritizing different values that both make sense but can’t be simultaneously maximized. Which is itself a useful lesson about modal space: sometimes you can’t have all possible worlds at once. Sometimes you have to choose what kind of choosing you want to do.

Anyway, I’ve reloaded this essay fifteen times and this is the version where I made the Undertale reference, so I guess we’re committed now.

V. Causality and Truth

Okay, this is where things get technical, and also where I’m going to lose half my readers because they’re going to go play Minecraft instead of finishing this essay. I understand. I respect it. But come back when you’re done, because this is where things go wild.

Most online games are metaphysical realists and they’re not shy about it.

In Minecraft multiplayer, there is a truth, and the truth lives on the server. Your computer is running a little simulation that’s basically your brain’s best guess about what’s happening, and then the server occasionally comes by and says “actually no” and your character teleports three blocks backward. This is called rubber-banding and it’s what philosophical realism feels like when you have 200ms ping.

This makes everything totally unambiguous. There are no interpretations, no perspectives, no “well from my reference frame.” The server said you died, you died. The server said that block is still there, the block is still there.

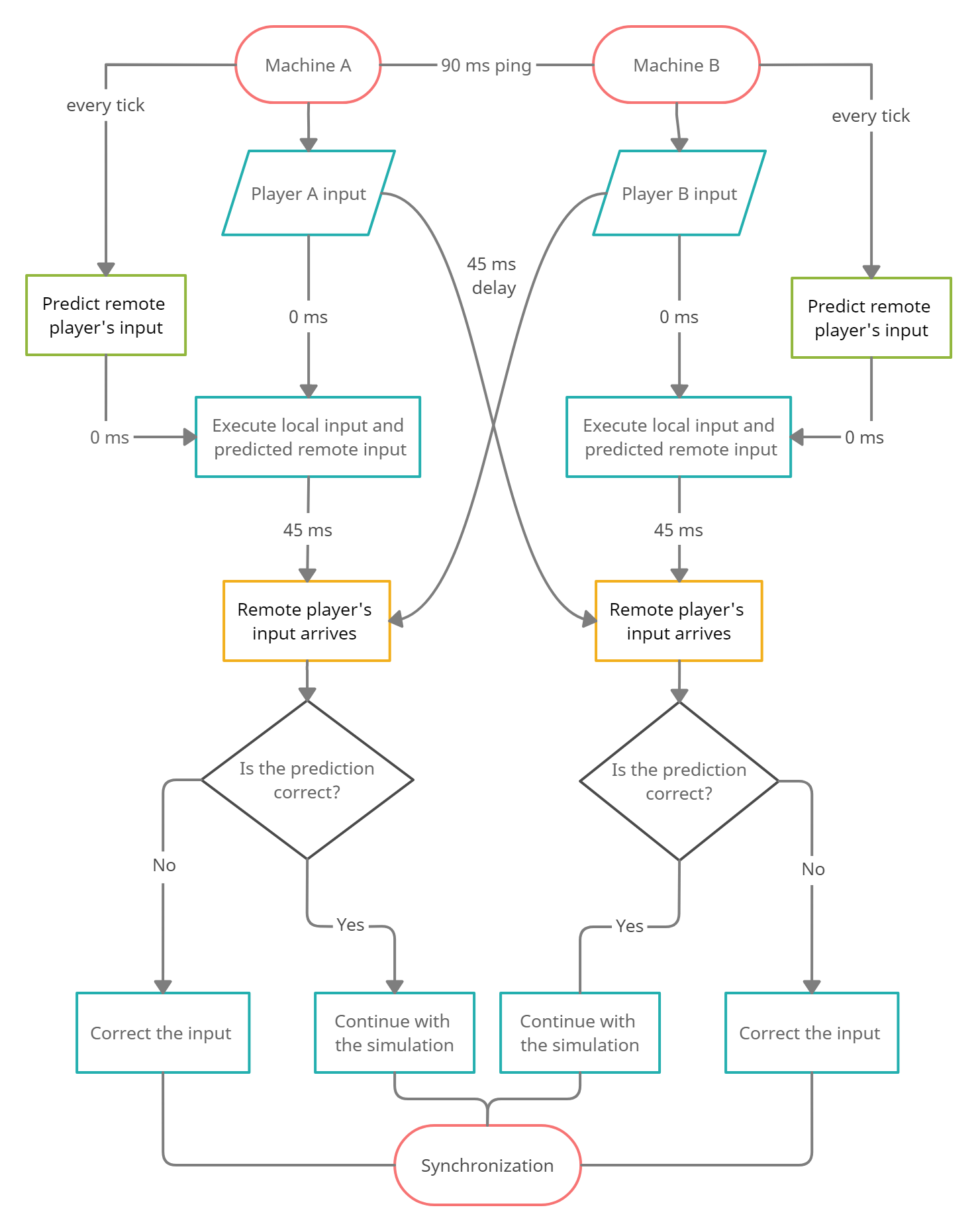

Fighting games present a particular challenge for online play: they require frame-perfect timing, where a single frame (1/60th of a second) can determine whether you successfully block an attack or get hit. But network latency means information about your opponent’s actions arrives late, often 3–10 frames after they performed them.

The traditional solution was input delay: the game waits for network confirmation before showing anything happening. This makes the game feel sluggish and unresponsive. You press the punch button, and your character punches 100 milliseconds later.

Enter rollback netcode.

In Skullgirls (and Street Fighter and a bunch of other 2-person fighter games), both players treat their own inputs as immediately true. If I press the punch button, my game says “okay, I punched” right away. But then information arrives from my opponent saying they blocked 50 milliseconds ago, which I didn’t know about because the internet. So the game rewinds time, re-simulates the last 50ms with the new information, and shows me the result. I did punch, but it turns out I punched into a block, we just didn’t know that until causality caught up with itself.

And what was happening in the meanwhile? It turns out I’ve been playing against a robo-doppelganger of you. And then, from the game designers’ point of view, hopefully it’s been doing a similar enough thing for the last few frames that there’s not much of a visual difference between where the robo-you was headed and the actual you now is.

It turns out that with a simple predictive model, and some smart animation design choices, this can be done in a way that is basically unnoticeable to either of us. Is that nuts? There’s one true past (eventually), but multiple nows, and they get reconciled after the fact.

If you go even further and stretch this serverless mutual-truth idea to a bunch of connections—just have players connected in some arbitrary topology of distributed peer-to-peer network, each running their own simulation—the metaphysical questions explode like a creeper in your house that you definitely put torches around but apparently not enough torches.

When some subset of players make incompatible updates to the world, whose version is real?

Different possible answers correspond to different theories of truth, and the fact that game developers have to actually choose one makes this way more concrete than any philosophy seminar. Here are some possible choices:

Latency-based priority: Reality belongs to whoever’s internet is fastest. This is obviously terrible as philosophy but it’s literally how a lot of peer-to-peer games work. In this universe, the fundamental nature of reality is determined by your ISP’s routing infrastructure. This suggests that Comcast has theological implications, but I’ll leave it to Scott Alexander to expound on its proper kabbalistic interpretation.

Global timestamps: There’s a universal clock and reality is whatever happened first according to that clock. This sounds reasonable until you remember that relativity is a thing and also good luck synchronizing clocks across the internet.

Eventual consistency: There is no single state, just local simulations that get close enough over time. This is basically Buddhist philosophy implemented in distributed systems. Everything is illusion, but the illusions eventually converge to something we can all work with, probably.

Voting/consensus: Reality is whatever most players agree happened. This is how cryptocurrencies work. It’s fascinatingly democratic and also means that reality is vulnerable to Sybil attacks. You can epistemologically DDoS someone by spawning enough fake players.

Nobody actually makes video games like this. Yet.

I’m not saying game developers are consciously doing philosophy when they implement multiplayer systems. I’m saying they’re forced to take positions on deep metaphysical questions whether they want to or not, because you actually can’t make a multiplayer game without having a theory of truth. It’s philosophy by other means, except the philosophers are getting paid and shipping actual products. Well, some of them.

VI. Hyperproperties and the metagame

Most games treat their laws the way medieval peasants treated natural law—fixed, eternal, handed down from on high (the developers). You can act within the world, but the world’s fundamental nature is not up for negotiation.

But some games said “what if the laws of nature were just… objects? What if we put them in the game and let you push them around?”

Baba Is You is the purest example of this and it will make your brain hurt in new and exciting ways. The laws of physics are represented by blocks spelling out sentences: “WALL IS STOP” means walls are solid. But the words are objects in the world that you can push around. Break up the sentence and walls stop being solid. Push the words to spell “WALL IS YOU” and suddenly you’re playing as all the walls. Push them to spell “WALL IS WIN” and touching walls beats the level.

The genius here is that laws become local, contingent, and destructible. They’re not transcendent rules—they’re just more stuff that happens to have special effects when arranged correctly. It’s a deeply Humean universe where regularities are just patterns we notice, not necessary truths, but in this case the patterns are made of alphabet blocks and you can kick them over.

There’s a second layer that most players don’t think about philosophically but definitely experience mechanically: the difference between in-game actions and meta-level actions.

Your character in Skyrim lives in a world with causality, physics, time. But you, the player, can pause the game, freeze time, adjust difficulty sliders, open the console and type tgm to toggle god mode. From inside the simulation these are miracles—violations of natural law. From outside they’re just… different kinds of input. Higher-level causes.

Players naturally distinguish “legitimate” actions (swinging sword, drinking potion) from “illegitimate” ones (using console commands to spawn items). This isn’t in the game’s code—the engine doesn’t care. It’s a social distinction we impose based on our intuitions about fair play and authentic experience. We’ve collectively decided that some causal interventions are kosher and others are “cheating,” even though they’re all just bits flipping in RAM.

And then how do we categorize game updates, patches, and mods?

When Blizzard releases a balance patch that changes how much damage Fireball does, is this the same game? The same world? Different communities have different answers! Some speedrunners insist on running specific patch versions. Some modding communities treat particular mod combinations as “the canonical experience” in a way that’s weirdly theological.

The question “is modded Skyrim the same game as vanilla Skyrim?” gets you surprisingly far into questions about world-identity and essentialism. It’s the Ship of Theseus from the inside out: if you change enough of the rules, at what point does it stop being the same world? Is it about the quest structure? The engine? The feel? Players have strong opinions about this and will fight about it on Reddit, although I’d personally prefer to watch Wittgenstein and Popper duking it out with fireplace pokers.

VII. Meaning-Making

Lastly, I’m of the strong opinion that for philosophy, games matter more than bare simulations: games come with normative structures attached. They don’t just show you a world—they tell you what counts as winning, losing, success, failure, a good run, a waste of time.

This is huge and weird and like everything else in this long ass post I don’t think we appreciate it enough.

The virtual reality world Second Life is basically existentialist philosophy as a platform. There are no goals. No win conditions. No “correct” way for you, or anyone else, to play. You’re radically free and also nothing you do matters except insofar as you decide it matters. It’s Sartre but with mediocre graphics and more furries.

Most games are the exact opposite—they’re deeply essentialist and teleological in a way that would make Aristotle nod approvingly. Health potions have the essence of healing. Keys have the purpose of opening doors. Quest markers point at where you “should” go. The world has a telos—there’s an end boss, a final level, a narrative conclusion—and everything is oriented toward that ultimate purpose. The systems themselves implement a theory of value and meaning.

Ian Bogost calls this “procedural rhetoric“—the way game mechanics make arguments about how reality works. Not through cutscenes or dialogue, but through the experience of playing.

Papers, Please is the best example I know. You’re a border guard checking immigration documents. The game makes you process people quickly (you need money for food) but also accurately (you get penalized for mistakes). Then it adds more rules. Then contradictory rules. Then rules that require you to separate families or deny entry to obviously sympathetic people.

The game doesn’t tell you that bureaucratic systems force impossible moral trade-offs. It makes you feel it through the mechanics. You experience the vice tightening, realize you’re going to fail someone (your family or the refugees), and understand viscerally how systems can force good people into bad choices. The argument is in the game design itself.

And in multiplayer games, you get emergent social ontology on top of everything else.

EVE Online gives players a relatively neutral physics engine and says “okay, go build civilization.” And they do! They create corporations, alliances, complex economies, political systems, wars, betrayals, the most elaborate heist in gaming history. The meaningful stuff—the wars, market crashes, legendary scams—wasn’t scripted. It emerged from thousands of players pursuing their own goals in a shared ruleset.

This is social construction happening in real-time. The game’s code defines what’s physically possible, but players define what’s socially real. Corps and alliances aren’t in the base mechanics—they’re emergent social structures that became “real” because enough people treated them as real. Money is backed by collective belief. Reputations matter because communities enforce consequences. It’s all the weird stuff from social ontology, playing out in a million different environments.

Huh, what do I do with this.

Okay, I’ve spent 5000 words convincing you that video games are secretly metaphysics labs. Assuming I’ve succeeded (or you’re still reading out of politeness), what are the actual applications?

A. Game design: If you’re making games, the metaphysics literature is full of ideas you could implement. What if different players experienced time at different rates? What if groups of players inhabited partially incompatible realities that occasionally synced up? What if truth was computed by NPC consensus rather than fixed by the server? Framing these as metaphysical questions makes them easier to explore systematically instead of just stumbling into them.

B. Teaching: Undergrads have way more hands-on experience with virtual worlds than with philosophy texts. It’s easier to explain modal ethics through Undertale’s save system than through abstract possible worlds semantics. Easier to contrast essentialism and existentialism through Zelda vs Minecraft than through Aristotle vs Sartre. I’m not saying replace the classics—I’m saying give people a hook they can grab onto before hitting them with the heavy stuff.

And you can do a lot more than just enliven dull texts with the existing video game corpus. For any sufficiently coherent philosophical idea, there’s probably some way to model it in gameplay. If you can do this for Deleuze, I’ll give you a thousand bucks. Just don’t dumb it down, or I’ll fucking kill you.

C. Philosophical research: With modern AI coding tools, philosophers could specify metaphysical structures they’re interested in, then have the tool chew on it for a bit and spit out toy implementations to play with. Which parts of your theory can you make precise enough to hand to a game engine? Where do your intuitions break when you actually try to live inside your model for an hour? This could be really valuable feedback for theory development.

D. Agent foundations in AI safety: Game environments are already central to AI research. Agents that work great in centralized, server-authoritative worlds might behave very differently in messy, partitioned networks with no global truth. Making the metaphysical assumptions explicit—what kind of causality does this environment assume? what kind of truth?—could help us build better test environments and understand where our agents might fail. Designing environments is the complement to designing agents; I think progress in understanding conceptual game design would speed progress in understanding agent design as well! Talk to me if you’re interested in figuring out where to go with this.

Conclusion

Look, I know this essay has been long. I know some of you are thinking “this is just a fancy way to justify your gaming addiction.” Maybe! But also, I think there’s something real here.

For most of human history, we had one reality and we lived in it. Philosophy developed elaborate tools for thinking about that reality, but the tools were all theoretical. Thought experiments, armchair reasoning, careful argumentation about worlds we could never visit.

Now we have the ability to spin up new worlds, with different rules, and actually live in them for long enough to build intuitions. We’re teaching ourselves to be ontological chameleons—to switch fluently between incompatible metaphysical frameworks depending on which game we’re playing. Kids are casually navigating four different spatial ontologies before breakfast and don’t even notice it’s weird.

This is either going to be really useful or really confusing when we eventually encounter alien intelligences with radically different baseline metaphysics. But either way, we’re building a library of possible agencies and possible realities, one game at a time.

Also Factorio is really good and you should play it but maybe not if you have anything important to do in the next 48 hours.

I’m probably going to write more about the causality stuff, because I think things like rollback netcode are genuinely some of the most interesting things happening in metaphysics right now and nobody seems to have noticed. But that’s for next time.

tags: philosophy, - video - games, - mmo, - metaphysics

Comments powered by Talkyard.